real

the barked project

In a rapidly changing world, we document the rarest of ancient trees to preserve their legacy. Embrace the real.

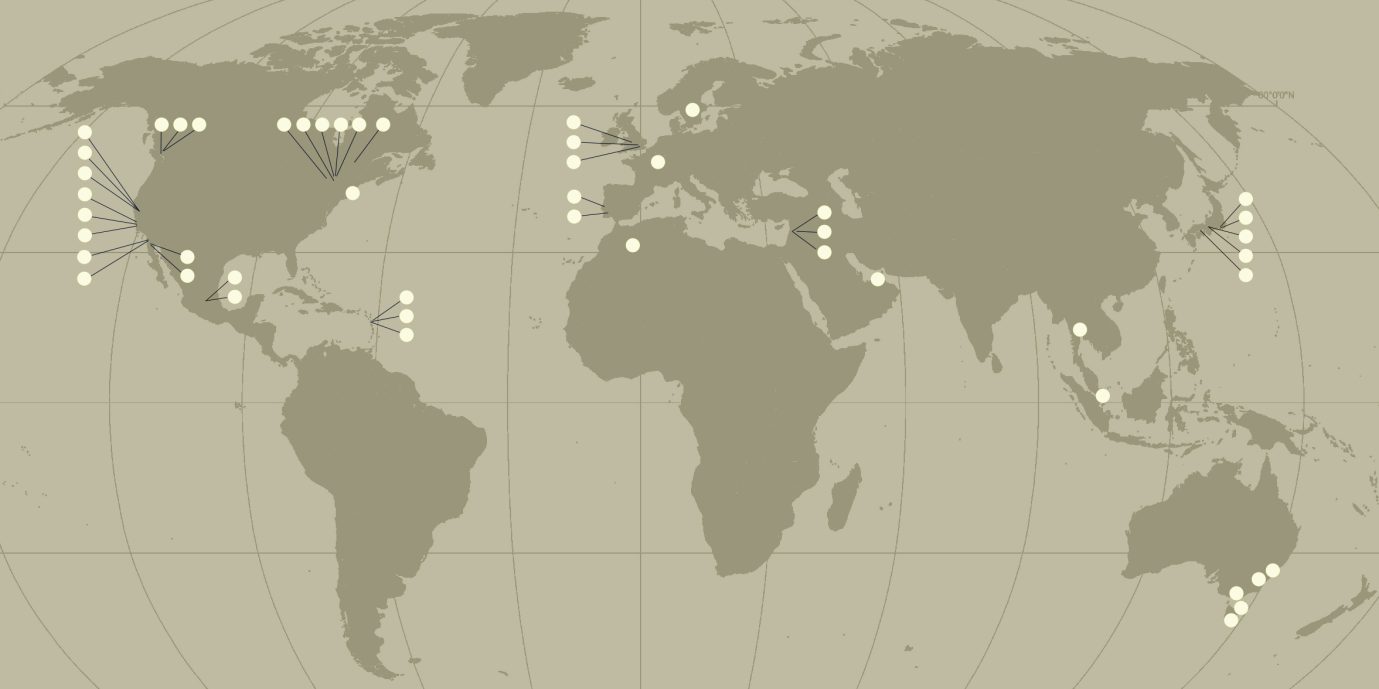

Our tree expeditions to date

Ancient trees and forests are windows into the beauty and memory of an earlier time. They are living connections to the earth's distant past and its possible future.

The high-definition bark images by Robert Ouellette are a meditation on time and place. He reconnects us to the intimate details of majestic trees through large, sublime prints and environments.

Contact us for limited edition prints and sublime environments.

Seeing the forest through the trees

Trees are the world’s oldest living beings. Their majestic beauty is a spiritual connection to an earth that sustains us physically and emotionally. Ouellette travels the globe documenting the rarest of these ancient treasures to preserve their legacy. A tree's bark tells the story of its life. Collectively, the images document the fragility of nature in an age of massive social and environmental change.

The bark images are made using advanced photographic tools. Where possible, the entire girth of a tree is captured in sections. The high-definition results are digitally stitched together to make seamless images. In a noisy, frantic world artist and architect Robert Ouellette's minutely detailed works are an antidote to a culture of spectacle.

The barked images and related artifacts are available in a number of different forms. Supporters of our mission, fine-art collectors, designers, and institutions interested in carrying our work please contact us for more information.